Transport Funding: Who Gets the Big Piece of Pie?

The U.S. Department of Transportation’s second round of stimulus funding for infrastructure development exposes a widening gap between U.S. roads, rails, and bridges and government special interests.

The Good, the Bad, and the Fads

Atlanta’s downtown streetcar project pulled away as the big winner in the U.S. Department of Transportation’s (DOT) second round of the Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) sweepstakes announced in October 2010. The new commuter system, which will operate four trolleys and 12 stations in connection with the existing Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority light rail system, received $47.7 million in grant money.

In Fort Worth, Texas, the Tower 55 Multimodal Improvement proposal ($34 million), aimed at alleviating freight bottlenecks at an intersection between the Union Pacific and Burlington Northern Santa Fe railroads, finished a distant second— and the disparity in funding reveals a much broader chasm in government’s ability to practice fiscal discretion.

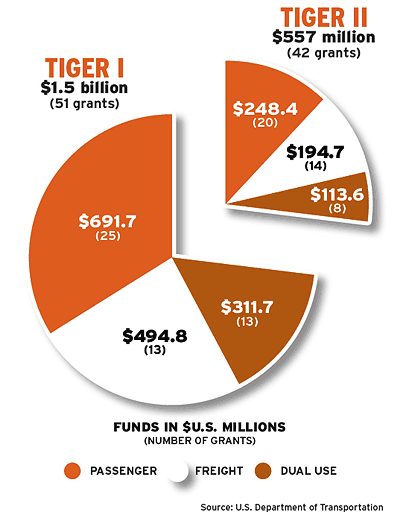

The DOT awarded nearly $600 million in grants to 42 capital construction projects and 33 planning projects from a pool of 1,000 applications valued at $19 billion. When transportation officials introduced TIGER subsidies almost two years ago— as legislated by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009— they rolled out 51 grants worth $1.5 billion.

Roughly 29 percent of the TIGER II funds were approved for road projects, 26 percent for transit, 20 percent for rail, 16 percent for ports, five percent for planning projects, and four percent for bicycle and pedestrian right of ways, according to the DOT.

But whatever the perceived balance in terms of transport allowances across modes, officials have made it clear that public-facing commuter facelifts— when job growth and unemployment are arcing in opposite directions— take priority over much-needed freight infrastructure development.

Of the 42 capital projects awarded grants, 20 (48 percent) are purposed for passenger transport, 14 (33 percent) for freight projects, and eight (19 percent) for dual use (any project that contributes to both freight and passenger improvements). In terms of funding, freight proposals received $194.7 million in direct aid, passenger initiatives were allotted $248.4 million, and $113.6 million was spent on shared initiatives.

This distribution of funds is not an anomaly. The initial TIGER dispersal in February 2010 reveals the same imbalance. Nearly three times as much money was doled out, but of the 51 grants, 25 passenger-oriented projects raked in $691.7 million, 13 freight projects received $494.8 million, and 13 dual-purpose proposals accounted for $311.7 million.

One positive footnote is that the two grants in excess of $100 million were both directed toward freight infrastructure efforts— the CREATE Program Projects in Chicago and the Crescent Corridor Intermodal Freight Rail Project in Tennessee and Alabama.

Freight Doesn’t Rate

The imbalance in freight transportation spend, as dictated by the DOT, will only stoke wildfire debate about the dire condition of U.S. roads, bridges, rails, airports, ports, and their surrounding infrastructure. In October 2010, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s first-ever nationwide and state-by-state Transportation Performance Indexes revealed a significant decline in how the country’s transportation network is serving the needs of the economy.

From an economic development perspective, a well-developed system for moving cargo is the dangling carrot that entices investment, attracts manufacturing, and creates jobs— this, in turn, stimulates consumer spending for automobiles, walking shoes, and bicycles. Allocating nearly $50 million for a downtown trolley system exposes a severe lack of transportation leadership at the federal level and the need for a national transportation policy that can provide governance for distributing transportation funding such as TIGER.

While the DOT reports that only four percent of the 2010 grants will be directed toward bicycle and pedestrian projects, in fact, 15 of the 42 winning proposals (36 percent) have provisions for bicycle and pedestrian enhancements. The 47-page press documentation publicizing the TIGER II recipients contains 45 references to “pedestrian,” 41 to “freight,” 37 to “bicycles/bikes,” and three to “cargo.” Observers need look no further than the fine print to gauge the government’s priorities.

Even more telling, $20 million has been set aside for California’s Crenshaw/LAX Light Rail TIFIA Subsidy in Los Angeles; $10.2 million appropriated for the East Bay Pedestrian and Bicycle Network in Alameda and Contra Costa counties; and $10 million for the San Bernardino Airport Access plan. All three projects, totaling more than $40 million, are primarily dedicated to public transit improvements. Only the airport initiative will have a measurable impact on alleviating freight network congestion in the area.

The fourth TIGER II recipient from California, the Port of Los Angeles’ West Basin Railyard development ($16 million), will have a direct impact on cargo movement, connecting on-dock railyards to the Alameda Corridor.

With the first TIGER pass, two of California’s four winning applications— the Alameda Corridor and the Green Trade Corridor/Marine Highway— were specifically directed at cargo improvements. So the success of California’s earlier considerations and priorities may have swayed the state’s most recent transportation funding targets and the DOT’s decision-making.

Still, California ranks among the worst states in terms of transportation performance as it relates to economic value, says the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Light rail systems, pedestrian walkways, bike paths, and better access to a regional airport are cosmetic fixes that do little to resolve fundamental infrastructure problems beyond helping travelers avoid traffic.

In Illinois, priorities are similarly slanted. The grant awarded to the Warehouse District Complete Streets project in Peoria allows city officials to “pursue plans to revitalize the area through mixed-used development, combining housing with shopping and work destinations,” according to the DOT. As far as transportation investment, money will go toward enhancing the local road system “to encourage walking trips through sidewalk and streetscape improvements.” Among the project’s highlights? It will bring dilapidated and non-existent sidewalks into a state of good repair.

Rural vs. Urban

The criteria the DOT used in vetting these recent grant applications remain largely unchanged from the first TIGER-go-round. Officials made one concession to set aside $140 million for rural infrastructure development, but approvals were based on shovel-ready projects, return of investment, innovation, and partnership.

The DOT’s rationale for prioritizing rural development also raises a few questions— for one, how it defines rural. Seventeen of the grants awarded in TIGER II were designated accordingly, including Oregon’s statewide Electric Vehicle Corridor, which will build 42 electric-charging locations along Interstate 5. Many of these sites will be concentrated in Portland, Eugene, Salem, and Corvallis. Another rural project is Moscow, Idaho’s proposed Transit Center. Moscow is a city with a population of 23,000 people.

Less-populated areas generally have fewer congestion problems and possess better transportation resources simply because they have to in order to remain competitive. Modal accessibility and efficiency are necessary incentives for businesses locating industrial facilities farther away from demand centers. It’s why North and South Dakota, Nebraska, and Montana are the top four performing states according to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s transportation index.

Densely populated areas, by contrast, often have the greatest transportation infrastructure needs in terms of moving freight and people. So improving commuter services in a major port city— thereby helping to alleviate traffic congestion— would better serve the interests of the greater national good than a new light rail transit system in a “rural city” where a growing percentage of the populace drives electric cars.

Why make a distinction between rural and urban transportation requirements? If there is an immediate and deserving need, it should be met.

The DOT’s TIGER II allocations are likely to spread further unease among transportation and logistics industry constituents— but one positive trend emerges among the 2010 grant recipients. Seven of the 42 requests were awarded to port authorities, totaling nearly $95 million, or 17 percent of the available funds. The American Association of Port Authorities’ goal was 25 percent.

In this regard, the TIGER II distributions reflect a considerable progression from the first round of awards, when port-related infrastructure projects received only eight percent of the $1.5-billion kitty. Other sectors, such as transit, highway/bridges, and pedestrian/bicycle, collected nearly 67 percent of the pie.

With port capacity, congestion, and labor shortages latent concerns in the United States, investing in and developing rail/intermodal infrastructure is one critical step in expediting cargo throughput, moving freight off heavily trafficked roadways, and working toward a greener business environment.

For now, however, this most recent round of TIGER funding, and the lion’s share of investment directed toward special interests that have little bearing on the country’s best interests, will do little to elicit a roar from an economy that is otherwise whimpering.

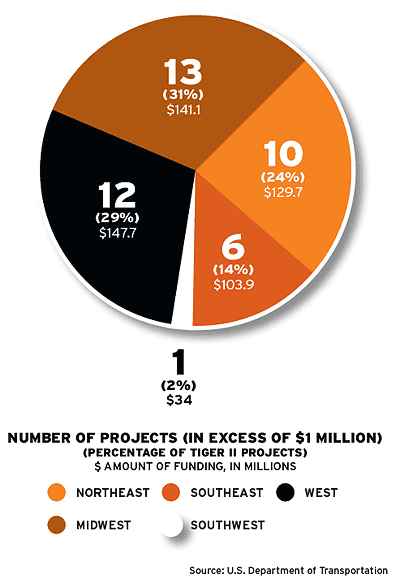

Mapping the Money

Not only is there a discrepancy between government funding for public-facing commuter facelifts and freight infrastructure development, there’s a regional discrepancy as well. The Midwest and West get the lion’s share of TIGER II funding, followed by the Northeast and Southeast. The Southwest gets far less funding than any other region.

Source: U.S. Department of Transportation

Keeping an Eye on the TIGER

In two rounds of transportation infrastructure stimulus spending, the U.S. Department of Transportation has distributed more than $2 billion across nearly 100 capital improvement projects. Given the economic climate and the condition of U.S. rails and roads, the disparity between funding for public transport and freight transport is remarkable. To date, two-thirds of TIGER funds have been directed toward passenger transportation interests.

Source: U.S. Department of Transportation

The Good, the Bad, and the Fads

At the turn of the 20th century, streetcars and bicycles were common in fast-growing urban areas all across the United States. In fact, the widespread popularity of cycling literally paved the way for U.S. road development.

Now, as century-old bridge, rail, and road infrastructure lies waiting for much-needed investment, this pair of transportation fads from the past is making a comeback.

Two of the top four grant recipients in the second round of TIGER funding, totaling $73.7 million, are for streetcar projects in Atlanta and Salt Lake City. More telling, 15 of the 42 winning proposals have provisions for bicycle and pedestrian enhancements, while only 13 are dedicated specifically to freight transportation.

To provide a better picture of how U.S. tax dollars are being put to work, here’s the DOT’s rundown of notable transportation projects that received TIGER II funding.

The Good

Port of Miami Rail Access

Project Cost: $46.9 million TIGER Funding: $22.8 million

The grant will help establish intermodal container rail service to the Port of Miami by building an intermodal yard and making necessary rail and bridge improvements. Specifically, the project will upgrade track, signals, and switching between the Florida East Coast Railroad Hialeah railyard and the port.

Port of Los Angeles: West Basin Railyard

Project Cost: $125.8 million TIGER Funding: $16 million

The West Basin Railyard project will construct an intermodal yard, including staging and storage tracks that connect on-dock railyards with the Alameda Corridor. It will also include a railyard for the short-line railroad serving Union Pacific, Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF), the Port of Los Angeles, and the Port of Long Beach.

Tower 55 Multimodal Improvement Project (Fort Worth, Texas)

Project Cost: $91.2 million TIGER Funding: $34 million

Tower 55, a major rail and traffic bottleneck, is an intersection in downtown Fort Worth where Union Pacific and BNSF railroad lines cross. The project will improve the flow of train traffic through this intersection by adding a north-south track and installing new signals and a new interlocking system.

Coos Bay Rail Line Rehabilitation (Oregon)

Project Cost: $14.6 million TIGER Funding: $13.6 million

The Port of Coos Bay project will rehabilitate the track structure of the 133-mile Coos Bay Rail Link, which closed in 2007 as a result of deferred maintenance.

The Bad

Dilworth Plaza and Concourse Improvements (Philadelphia)

Project Cost: $55 million

TIGER Funding: $15 million

The Dilworth Plaza and concourse improvements project will upgrade the deteriorated public plaza adjacent to Philadelphia’s City Hall into a major gateway for public rail, bus, and trolley transportation. The project will also create more green space and incorporate features facilitating compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act. The project enjoys substantial support from surrounding offices and hotels.

Warehouse District Complete Streets Project (Peoria, Ill.)

Project Cost: $37.4 million TIGER Funding: $10 million

The money will help the City of Peoria pursue plans to revitalize its downtown area through mixed-used development, combining housing with shopping and work destinations. The project will improve the local road system to encourage walking trips through sidewalk and streetscape enhancements in support of mixed-use development on the 185-acre site.

New Haven Downtown Crossing

Project Cost: $31.7 million TIGER Funding: $16 million

The New Haven Downtown Crossing project will convert Connecticut State Route 34 from a limited access highway to urban boulevards with road, streetscape, bicycle, and pedestrian enhancements, as well as reconfigure local street connections.

The Fads

Atlanta Streetcar

Project Cost: $72.2 million TIGER Funding: $47.7 million

The project, which connects to the existing MARTA light rail system, will operate 2.7 miles of track and four streetcars in a loop between 12 stations.

East Bay Pedestrian and Bicycle Network (Contra Costa and Alameda Counties, Calif.)

Project Cost: $43.3 million TIGER Funding: $10.2 million

The East Bay Pedestrian and Bicycle Network will close several gaps in the nearly 200-mile bicycle and pedestrian trail system serving the 2.5 million residents of Contra Costa and Alameda counties in California. The project will separate bicycle and pedestrian traffic from automobile traffic, and connect to transit facilities.

Sugar House Streetcar (Salt Lake City)

Project Cost: $55.6 million TIGER Funding: $26 million

The Sugar House Streetcar project will include a two-mile streetcar line between an urban arterial route and Interstate 80, connecting the regional commercial center and redevelopment area to the TRAX light rail system. When the project opens in 2013, daily ridership is estimated to be approximately 3,000, and is projected to rise to 4,000 by 2030. The Salt Lake City metro area has a population of 1.1 million people.

Source: U.S. Department of Transportation