Bulk Materials Handling: Conveying the Non-Conveyable

The supply chain shift to e-commerce fulfillment presents a cumbersome materials handling challenge for bulky and oversized items that can’t properly run on automated infrastructure.

Over the past five years or so, Vecna Robotics has worked with companies experiencing a sustained jump in e-commerce shipments of non-conveyables—products such as furniture and appliances that are too large or bulky to fit within standard sortation equipment.

These items used to account for a small percentage of shipments but now “push 12 to 15% of total volumes,” says Matt Cherewka, director of business development and strategy with Vecna.

The jump in e-commerce sales of non-conveyables has disrupted many organizations. For instance, online orders for stationary bikes, treadmills, and weights spiked 55% between Jan. 1, 2020 and March 11, 2020, according to the Adobe Digital Economy Index.

Online sales of home furnishings have also jumped. In January 2020, eMarketer estimated online sales of furniture would reach $76.8 billion for the year. By December, it had boosted its estimate to $92.3 billion, up 20%.

A Bright Spot with Challenges

In many ways, the growth in sales of non-conveyables has been a bright spot during a period when many businesses struggled. At the same time, handling these products presents unique challenges. True to their name, they don’t fit within standard automation equipment and often have to be handled manually.

“Manual processes may have worked when these products represented a small segment of sales,” says Bruce Bleikamp, director of product management with Material Handling Systems, a provider of turnkey material handling automation solutions. “Companies could simply throw people at the problem.”

As e-commerce sales of non-conveyables have increased, that’s becoming less practical.

Moreover, even though a manual approach worked in the past, it was rarely ideal. Manually moving non-conveyables increases the risk of damages and returns, boosting costs for shippers and logistics providers, says Chris Randall, vice president of revenue with Cymax Group, which offers an online platform that provides seamless customer acquisition, merchandising and logistics capabilities.

Turnover in warehouse positions focused on moving non-conveyables tends to be high. That means less experienced people often fill these roles, which can increase the rate of injuries and mistakes, Bleikamp says. And warehouse operators now have the added challenge of trying to maintain COVID-19 social distancing protocols, even when several people are needed to move a single non-conveyable.

While moving furniture, appliances, and other non-conveyables presents challenges even in more traditional supply chains, “the complexity in the supply chain jumps once orders go direct-to-consumer,” says Jeff Christensen, vice president of product with Seegrid, an autonomous mobile robot developer. “The flow of material is much more complicated because it’s much more granular.”

One order might include a washing machine, the next, a book, and the third, a pair of running shoes. The variety eliminates efficiencies of scale. “You can’t fill a truck with 20 washing machines, as you could when moving items to a store,” Christensen says.

Moreover, consumer expectations for efficient, safe, and timely delivery extend to all orders, whether for a t-shirt or a bathroom vanity.

And, despite their size, non-conveyables can require just as much care as, say, bottles of perfume. Rowing machines, for instance, “require heavy, large, and long packaging, and their advanced technology makes them delicate,” Randall says.

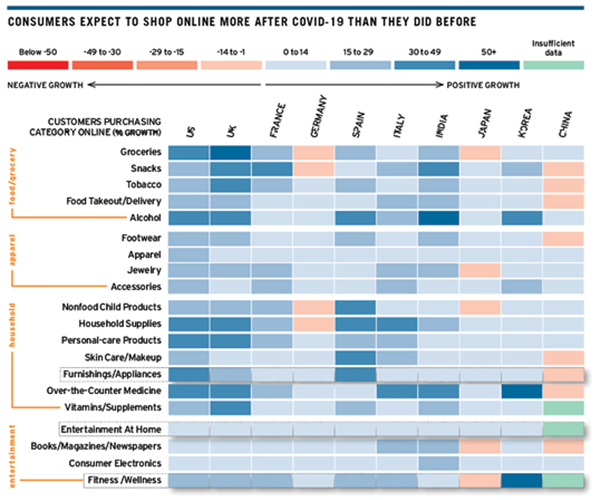

The challenges associated with non-conveyables are likely to continue, as e-commerce sales of these products show no signs of stopping. About half of U.S. consumers expect to maintain higher levels of online shopping for furnishings and appliances going forward, McKinsey reports (see chart).

Many consumers began online purchasing with smaller ticket items. “Since then, the value, physical size, and quantity of items purchased online have trended up alongside consumer confidence with the process,” says Mark Stothers, product manager with Fives Intralogistics Corp., an automation equipment provider.

Turning to Flexible Automation

Given these trends, manufacturers and logistics providers have to “figure out a way to take an inefficient load and come up with an efficient method of transport,” Christensen says.

Their approaches increasingly encompass “flexible automation,” says Christian Dow, executive vice president of membership and industry leadership with MHI, a materials handling association. The idea is to employ technology that expands the range of products that are considered standard and to which automation can be applied.

Many companies are turning to technology solutions such as automated guided vehicles (AGVs) and autonomous mobile robots (AMRs). The AGV/AMR market is expected to cross the $5 billion mark by 2026, at which point these devices will have captured more than 18% of the overall warehouse automation market, according to Research and Markets.

“Robots hit the sweet spot,” Christensen says. By eliminating some manual operations, they can reduce product damage and injuries, while offering flexibility in what’s moved and how frequently.

The terms AGV and AMR are often used interchangeably, but the two differ. AGVs travel with the aid of magnetic strips or wires and are used where movement is structured and monolithic. AMRs, in contrast, can work in dynamic environments with autonomous navigation. They use facility maps to find alternative paths if obstacles block defined routes, according to research firm LogisticsIQ.

Most product categories have seen more than 10% growth in their online customer base during the pandemic, and many consumers say they plan to continue shopping online even when brick-and-mortar stores reopen. That means the challenges associated with delivering e-commerce orders of bulky and oversized products such as furniture, appliances, and fitness products will continue.

Source: McKinsey & Company COVID-19 Consumer Pulse surveys,

conducted globally between June 15 and June 21, 2020

Moving with Robots

To move non-conveyables, an AMR or AGV typically is placed underneath a cart, which is then loaded with one or more items. Many can handle up to several thousand pounds; some can hold up to 10,000 pounds.

AMRs also allow for multiple loading and unloading areas, enabling operators to distribute work across a warehouse. “They don’t landlock areas of the facility like conveyors can,” Bleikamp says.

In addition, once an area is mapped, the vehicle can go where it needs to. The operators still control the vehicle’s route. But with no fixed infrastructure like wires or tape, the area in which an AMR can travel is “wide, flexible, and easily changed,” Bleikamp says.

Another benefit? A smaller footprint and ability to turn within their own dimensions make AMRs ideal for many tight environments. AMRs also tend to operate more predictably and methodically than forklifts. “The controlled travel makes them more stable,” Christensen says.

Companies increasingly ask MHS to pursue these new technologies. “The need for them to run their businesses effectively with a general lack of labor is a growing issue,” Bleikamp says.

In addition, companies building new facilities are allowing for more open dock space, wider transport aisles, and higher ceilings, all of which enable them to take full advantage of technologies like AMRs.

Some robots, including Vecna’s, can adapt to their environment as they navigate, identifying and then taking the most efficient route.

“They plot multiple potential routes and choose the most efficient option based on factors like distance, traffic, and location of the stops along the route,” Cherewka says. When necessary, they can reroute on the fly.

Vecna’s orchestration engine can balance overall demand and dynamically assign more pickup requests to tuggers as capacity becomes available, boosting the tuggers’ efficiency. (Tugger train systems consist of tugger carts that are towed by an operator acting as a locomotive to transport materials in the warehouse.)

Software that directs humans alongside robots and enables multiple robots to work together, like a forklift loading a tugger, is just hitting the market now. Cherewka expects implementations to start over the next year or so.

Along with tools that facilitate transportation, technology also helps shippers and logistics providers identify more efficient facility configurations.

For example, some warehouse management systems can identify the products that move most frequently, the high-traffic areas within a warehouse, and the time required to store, pick, pack, and ship goods. By assembling this information, they can help design a warehouse layout that reduces bottlenecks and ensures popular items are more easily accessible than those that turn over more slowly.

Remaining Obstacles

For all the progress that has been made in handling non-conveyables, challenges remain. While AGVs and AMRs can transport a range of non-conveyables, many of these products still need to be manually loaded and unloaded. “It’s partial automation,” says Dwight Klappich, vice president and analyst with research firm Gartner.

Even so, this hybrid model of using AGVs and AMRs to transport goods, while using employees to load and unload, will continue to grow.

Predicting when robotic arms capable of loading and unloading individual non-conveyables will hit the market is difficult, given their nonstandard shape and size, weight and bulkiness, and range of materials that make up the universe of non-conveyables. For instance, while a box typically will maintain its shape during handling, a roll of carpet is more apt to collapse.

“Making a robotic system that is capable of adapting to all non-conveyables will take some time,” Cherewka says.

Implementation Guidelines

Technology like AGVs and AMRs can automate the transportation of non-conveyables, reducing manual handling and the errors, injuries, and product damage that can result. The following guidelines can help in optimizing the use of the technology.

1. Determine if it’s worth the time and money to automate. Even though these technologies tend to be less expensive than many large sortation systems, it’s still harder to justify the investment for products that sell in low and inconsistent volumes.

2. Clearly define the solution you need. How will you dispatch the vehicle? How will you prioritize activities? What is the goal? For instance, if you’re currently handling a non-conveyable a dozen times, maybe you’ll try to cut that by 75%.

3. Start small, gain experience, monitor the solution’s operation in your facility, and grow steadily. One benefit of most flexible automation technology is that you can add pieces relatively easily. Often, it’s possible to ramp up within hours or days.