Today’s Distribution Center: You Say You Want an Evolution?

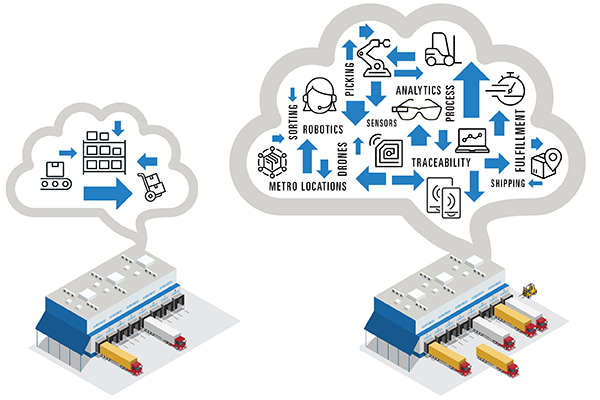

Today’s distribution centers provide far more than just short-term storage and cross-docking. By locating closer to urban areas, leveraging technology, and adding amenities to attract skilled workers, DCs are morphing to accommodate e-commerce demands and rapid delivery expectations.

Hitting the Locker Room

UPS Gets in the Bike Lane

As businesses strive to accommodate customers’ expectations for ever-faster delivery times, many are focusing on enhancing and improving their distribution centers (DCs). “I see distribution centers taking on a more critical role,” says Tracie Longpre, vice president, supply chain with Applied Industrial Technologies,a Cleveland-based distributor of MRO supplies, tools, and industrial equipment. “Industrial consumers have become conditioned to want only what they need, exactly when they need it.”

To meet this expectation, products have to be stationed closer to the customer. “Applied Industrial continues to expand the breadth of products in its distribution centers, and to process product through DCs more rapidly,” Longpre says. That includes daily overnight deliveries from the DCs to local service centers.

Companies with DCs that can move a greater range of products quickly and cost-effectively “can create a competitive advantage,” says Mike Marks, managing partner with Indian River Consulting Group. “They can make more profit at the same selling price.”

Retooling a distribution center is not easy, however. Not only must inventory move more quickly, but it moves in larger volumes of small orders—fewer pallets and more eaches—which boosts complexity. Even five or 10 years ago, distribution centers might house several thousand SKUs. Today, many hold tens of thousands.

“There’s pressure on DC operations to pick, process, fulfill, and ship orders quickly, even as the number of orders has grown,” says Chris Merta, product manager with The Raymond Corporation, a warehouse solutions provider.

One way to meet these goals is to locate more products in distribution centers that are near or in urban areas. This has the added benefit of providing access to larger numbers of potential DC employees.

That solution runs headlong into another challenge: the lack of available land in many metro areas. To address that challenge, some companies are building up, rather than out, in multi-story DCs, says Bob Silverman, executive vice president, supply chain and logistics solutions with JLL, an investment management company specializing in real estate.

In 2017, warehouse owner Prologis broke ground on a three-story fulfillment center near Seattle, the first of its kind in the United States. Trucks can access both the first and second levels, which are geared to fulfillment. The third level is for light manufacturing and laboratory work, among other functions.

These types of facilities make up a tiny percentage of DCs within the United States, but their numbers are growing. That’s especially true in metro areas, such as San Francisco and New York, that are surrounded by water. “Companies that can’t find a location in the city wind up 90 minutes away,” Silverman says.

Along with metro areas, some DCs are opening near transportation hubs, such as the intersection of several interstates, says John Rosenberger, director of Global Telematics for Raymond. He points to the area around Pittston, Pennsylvania, which is home to numerous distribution centers. The closest metro areas are Wilkes-Barre and Scranton, with a combined population of about 120,000. However, Pittston sits astride several major highways, including Routes 81, 476, 84, and 380.

Another shift that impacts both DC size and location is the growing number of workers needed to handle item-level picking. “A distribution center for e-commerce fulfillment may require between three and 10 times the number of people needed in a DC that’s moving pallets or other bulk quantities,” says Rich Thompson, international director, supply chain and logistics solutions, with JLL. That translates to larger parking lots, break rooms, and other worker amenities.

Many retailers are also considering whether to repurpose space in some stores as DCs or online fulfillment centers. By doing so, they can address the challenges inherent in last-mile delivery, as they’d simply fill some orders from the DCs within their stores. In the end, most retailers likely will convert just a portion of their stores and maintain a brick-and-mortar presence.

DC Technology

To improve productivity within its DCs, Applied has focused on developing a lean culture, as well as technological opportunities that make financial sense. This includes warehouse management systems with advanced data management capabilities, logistics traceability, and analytics.Applied also is also investigating more progressive automated storage and retrieval systems and sorting capabilities, along with opportunities to digitize the supply chain.

“The benefits of having visibility to the entire network in real time are substantial,” Longpre says. “Visibility helps significantly reduce delivery lead times and optimize freight and inventory management.”

Ryder System, Inc., a supply chain solutions company, is combining robotics, drones, sensors, and wearables within three of its fulfillment centers. “The goal is to operate more productively and effectively,” says Alec Hicks, group director, solutions design.

For example, drones are able to complete a cycle count of an entire facility within three hours, rather than the customary two days, according to Ryder. And the use of smart glasses that project directions for order fulfillment within the user’s field of view cuts five to seven seconds off the time required to scan each inventory item.

The use of “goods to person” technology—small mobile robots that bring containers or products to pickers—is growing within many DCs. The reason? The workers picking orders can spend 70 to 80 percent of their time traveling and only 20 to 30 percent actually picking. “Goods to person technology seeks to greatly reduce or even eliminate the distances workers travel,” Silverman says. The result can triple productivity. While some of this technology has existed for a while, it has advanced even as its costs have dropped.

Inther Group also uses goods to person technology. Totes containing the SKUs needed to complete different orders arrive automatically at the workstation where order fulfillment will be completed. The workstation tells the operator what to pick and where to place it, boosting accuracy. The finished totes are automatically moved so the next task can start.

Currently, goods to person technology makes up about 95 percent of the “goods to” market, says Paul Hermsen, director with Inther Group. As more DCs and warehouses deploy robots as pickers, and as the picking robots become more capable, that ratio will shift.

One current obstacle to greater use of robots as pickers is variations in the products being picked. Robots today typically can handle rectangular cartons that weigh less than one kilogram (about 2.2 pounds). Products that are heavier, oddly shaped, or encased in plastic are more challenging.

Even existing DC technology solutions are providing more capabilities. For instance, distribution centers can leverage today’s warehouse management systems (WMS) to make better decisions around how much inventory to allocate to various sales channels, says Jeff Clark, executive vice president with ODW Logistics.

Say a pallet of socks needs to be divided between e-commerce fulfillment and retail replenishment. Advanced WMS capabilities can efficiently allocate the inventory between the channels to more accurately meet demand,

Over the past 10 years, box erectors, or machines that convert packaging material to boxes more efficiently than humans can, have increased in throughput and accuracy, even as the cost to install them has come down. “That makes the ROI much more appealing and palatable to companies looking to reduce labor requirements,” Clark adds.

Other traditional DC equipment, such as lift trucks, can be outfitted with vision-guided technology to automate some tasks. For instance, The Raymond Corporation integrates vision-guided technology in its automated lift trucks. The truck learns the operation it will be performing, such as moving a pallet of goods from one location to another, and then can replace manned vehicles for some tasks, leaving employees to handle more complicated jobs. “The technology optimizes both labor and assets to be most efficient,” Merta says.

As the number of people needed in DCs continues to grow, while unemployment remains at record lows, DC managers are struggling to find workers. “Finding labor is the biggest challenge today,” Thompson notes. One solution is to provide a more welcoming environment. “Everyone wants to work in a nice place,” he says. Many DCs, however, have been little more than brick blocks with few amenities.

That’s changing. Thompson recently toured a DC in Japan that boasted of its “human-centric design.” It featured an on-site child care center and rock-climbing wall, as well as eating areas that rival some restaurants. “We’ll see more of this in the United States,” he predicts.

Just as AirBnB and Uber upended the hospitality and rent-a-car industries, warehouse-on-demand firms aim to do the same for distribution centers and warehouses. “On-demand warehouse companies don’t own space, but match those looking for space with those that have access,” Thompson says.

“Our goal is to bring flexibility to supply chains,” explains Dave Galgon, director of network development with Flexe, an on-demand warehouse firm that offers access to more than 1,000 warehouses in North America.

Some retailers use Flexe to add capacity when the situation warrants it. Ace Hardware, for example, used Flexe to stock generators, box fans, and other larger items needed during weather emergencies in Florida, Georgia, and Texas. With this capacity in place, Ace was able to move shipments of these goods to areas affected by Hurricane Florence within 24 hours, on a Saturday. “We enable companies to position products closer to the market and provide better service,” Galgon says.

Will DCs Replace Warehouses?

While DCs play a more significant role within many supply chains, they’re unlikely to eliminate the need for warehouses. Some products require long-term storage, perhaps because the raw materials are available only at specific times, or manufacturers need to produce in large quantities to capture economies of scale.

At the same time, ever-shortening delivery windows mean distribution centers and the new technologies deployed within them will continue to play an increasing role within many supply chains. More distribution centers will use artificial intelligence (AI) to better predict demand, and thus reduce inventory carrying costs. “If you have good demand information, you don’t need lot of inventory,” Marks says.

For instance, AI tools can examine time-since-order (TSO) to determine trends in order placement, and then use this to fine-tune inventory levels.

One thing that won’t change is the DC’s ability to speed order fulfillment and deliver products quickly.

Hitting the Locker Room

In some metro areas, it’s not unusual for delivery trucks to park for hours outside a single apartment or office building while the driver delivers packages. That ties up streets and alleyways.

“Rethinking how to use the load/unload space is now necessary,” says Barbara Ivanov, chief operating officer with the Supply Chain Transportation and Logistics Center at the University of Washington. Ivanov is working with the city of Seattle to design a common locker system—essentially a tiny distribution center—where a delivery truck pulls up and unload its packages into separate, secure lockers. The recipients would receive an alert and have a set amount of time to retrieve their packages.

Early next year, Ivanov and her team plan to test common lockers within an eight-block area of Seattle. Previous testing has shown a locker can cut more than three-quarters of the time a delivery person otherwise would spend in a building.

UPS Gets in the Bike Lane

Some companies are thinking outside the distribution center when working to deliver products to customers quickly. For instance, electric bikes now power some of UPS’s brown delivery vehicles. In the United States, UPS has launched eBike programs in Pittsburgh and Seattle; worldwide, about 30 programs are up and running, says Kristen Petrella, a UPS sustainability spokesperson. Trailers and containers loaded with packages are attached to the pedal-assisted eBikes, which travel sidewalks and bike lanes. Each eBike can hold up to 40 packages.

To start their journeys, the eBike containers are attached to traditional UPS delivery trucks and then dropped off in a city center. Cyclists secure a container to their eBike, make deliveries, return the container when done, and attach the next container with packages ready for delivery. The same guarantees regarding package delivery apply whether packages are delivered via a cargo eBike or delivery truck.

“We’re finding interest for projects like this in cities across the country,” Petrella says.