Paving The Path To Progress

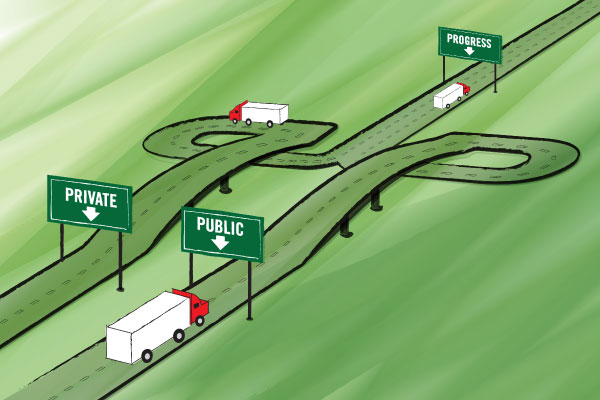

Can public-private partnerships transform America’s ailing transportation infrastructure?

U.S. Infrastructure: Worse for the Wear

Many of the roads, bridges, and transit systems that freight travels on each day were built decades ago, paid for by previous generations. Many more have outlasted their original design life and need to be repaired or completely rebuilt. The wear and tear we put on U.S. infrastructure is tremendous because we are a more prosperous and mobile country than we were when these systems were built.

It will take more than $2.3 trillion over the next five years to elevate U.S. transportation infrastructure to an acceptable level, according to American Society of Civil Engineers estimates. Following decades of under-investment, the federal stimulus plan was meant to disperse an estimated $50 billion to transportation projects based on proposals submitted by each state. As of June 2009, 1.2 percent of the stimulus funds were used for such projects, according to an October 2009 report from Business Monitor International (BMI) and the U.S. Department of Transportation.

PPPs Proliferate

In an effort to find more creative ways to fund transportation projects, state and local governments are turning to public-private partnerships (PPPs or P3s), government service or private business ventures funded and operated through partnerships between government and one or more private-sector companies. These agreements involve a contract between a public-sector authority and a private party, in which the private party provides a public service or project and assumes substantial financial, technical, and operational risk.

The use of this strategy has grown in the past two years, and the United States is fast emerging as the new frontier for PPPs, states BMI’s United States Infrastructure Report, Q4 2009, which forecasts the value of U.S. construction projects will reach nearly a half-trillion dollars. In 2008, 18 states were involved in introducing PPP projects in their legislatures.

PPPs come in a variety of shapes and sizes—ranging from small service contracts to multi-billion-dollar concessions and divestitures. In relation to the global PPP market, the U.S. share is still low. In 2006, according to statistics compiled by PriceWaterhouse Coopers, $9.2 billion in new PPP projects were closed in the Western Hemisphere, representing 14 percent of the total PPP projects worldwide. PPPs heavily concentrate in the transportation sector, which accounts for more than 60 percent of PPP projects worldwide.

According to research from Halcrow and McGraw-Hill Construction, 92 percent of U.S. state and local officials are "interested" in PPPs, and 71 percent claim PPPs are attractive under today’s economic conditions.

"We are faced with the great opportunity to lead with new thinking regarding infrastructure funding, particularly through vehicles such as PPPs," says Halcrow’s North American President Michael Della Rocca. "It is within our collective ability to redefine the funding, procurement, implementation, management, and renewal of our infrastructure assets and provide a network that will make a positive difference to people’s lives and to the broader wealth of America."

PPPs win private-sector support because they can help bring improvements crucial to supporting U.S. industry. "In order to remain globally competitive and move our goods and services effectively, we need to make infrastructure improvement a priority, and we need the financing to make that happen," says Harvey M. Bernstein, vice president, McGraw-Hill Construction. "PPPs can help fill this revenue gap, and state officials working with them are realizing the success they can offer."

Private investor involvement can also give projects a much-needed boost. "PPPs are powerful because they accelerate the delivery of projects by reducing the need for public expenditures and leveraging private markets," says Art Smith, chairman of the National Council for Public-Private Partnerships and president of PPP consulting firm Management Analysis, Inc.

Despite the benefits, the work that goes into making any PPP project a success can be a struggle for all those involved. Many transportation analysts agree the United States needs a new PPP paradigm that transfers more operational and financing risks to the private sector.

While dedicated public and private investment may set the wheels in motion, management issues associated with capital projects are increasingly complex for both public and private sector participants.

"PPPs are not a universal panacea for the country’s infrastructure needs; they only work when there is a reasonable opportunity for private partners to recoup their investment," says Smith. "The revenue stream can be created in many ways—through user fees; periodic government payments; or rights to utilize a government asset, such as land or facilities, for commercial purposes. But when a plausible revenue stream can’t be created, the success of a PPP is uncertain."

ppp Professionals

PPPs can be immensely complex arrangements that require an array of professional legal, financial, procurement, and engineering expertise. It’s important to ensure that both the public and private entities involved have the appropriate expertise. Frequently, this requires both sides to hire professional advisors who can lead them through the process and provide due diligence.

Without professional guidance, PPP projects can turn into a bumpy ride. One example is the Dulles Greenway in Northern Virginia. This privately owned and operated 14-mile toll road, which opened in 1995, connects Washington Dulles International Airport with Leesburg, Va. The roadway allows its users to avoid the congested public roads west of the airport.

The Greenway was built entirely with private capital. Under the partnership agreement, the private parties were to operate and maintain the road, retaining all the toll revenues, for 42 years. Then, the road would revert to the state. (This period has subsequently been extended to end in 2056.)

The private investors, however, overestimated the number of commuters willing to pay a toll, and from the outset revenue fell significantly below projections. The Greenway’s operators tried various strategies, such as cutting tolls and implementing a frequent driver program modeled after the airlines. But the losses continued to mount.

The private partners requested financial relief from the Commonwealth of Virginia. But the legislature noted that the private partners had agreed to accept the "demand risk"—the risk that use of the road would meet projections—so it refused to provide financial assistance. It did, however, pass a law increasing the speed limit on the Greenway to make it more attractive to potential users.

The project was eventually restructured, and the original private partners lost much of their investment. The new operators continued to invest in and improve the road, and maintain it as an attractive alternative to free public roads. In 2005, with the growth of the Washington, D.C., exurbs, the Greenway turned a profit for the first time.

"For the citizens of Northern Virginia, the Commonwealth, and the current operators, this PPP project is a success," says Smith. "But for the original private partners, who incorrectly assessed the initial usage of the roadway, this was a painful experience."

PPPs may not be the solution to every infrastructure need, but they do "work for a collection of reasons that benefit the public, customers, and, in our case, the railroads," says Bill Schafer, director of strategic planning for Norfolk Southern. "With the support of public partners, we can improve freight service to shippers and projects can come to fruition faster."

PPPs are a flexible instrument to meet governments’ transportation infrastructure objectives. Turn the page for a look at four PPP solutions in action.

Ohio’s Transportation Future: Interstate 70/State Route 29

The Interstate 70/State Route 29 (I-70/SR-29) intersection is becoming a major logistics hub in Ohio, attracting companies such as Kellogg’s, FedEx, Honda, and Target to establish warehouses and distribution centers in the area. "Developers plan to build additional DCs in the area, which will place even more demand on the intersection," says Scott Varner, deputy director for the Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT).

To meet this increased demand, the intersection requires major modernization and improvements, to the tune of an estimated $17-million price tag. ODOT and the local community are asking two area developers to commit $1.75 million each to help offset the cost.

The project, which is scheduled to begin as early as 2011, will be a key asset in Ohio’s business logistics strategy. "Ohio is approximately one day’s drive to 60 percent of the U.S. population," Varner says. "This project will improve access to I-70, which is a major freight highway."

While a PPP typically evolves out of a government’s desire to make an improvement or offer a service, the I-70/SR-29 project is an example of private entities—the developers—pushing the public ODOT to change and modernize an area.

ODOT is also looking to develop future PPPs. For example, in April 2009, it approved a provision under the state’s transportation budget to allow private companies to set up wind and solar power generating equipment on ODOT property. ODOT would use the power to light its highways, and could sell any additional energy to local power companies. The private companies would not pay for the ODOT space, and would maintain and operate all the local rest areas for a fee.

PPPs are important to the future of Ohio’s transportation infrastructure. "Transportation investment has the greatest return on investment for job growth and economic development, which is why it is an important part of the stimulus bill," says Varner. "In Ohio, a large portion of our state gas dollars are limited to use on highways and bridges, not other projects. Transportation investment and flexible tools such as PPPs can help meet that need."

Ohio is also looking to foster future PPPs through legislation that would create Transportation Innovation Authorities (TIAs), which are formed by local entities in a community or region to raise money for a proposed transportation investment, such as an intermodal center. The fees generated are used to fund the project.

Varner offers another example of how a TIA project would work: "Suppose a city offers property tax abatements for a development project," he explains. "In lieu of these taxes, a property developer could make a cash payment to the TIA to help fund the project. The private sector benefits from the public sector contribution. This is a great tool to foster public-private partnerships and regional cooperation."

States Coming Together: The National Gateway Project

Ohio is one of six states driving the National Gateway Project, a PPP notable for involving multiple public entities. Expected to cost $842 million, the project aims to create a more efficient rail route linking mid-Atlantic ports with midwestern markets, improving rail traffic flow between these regions by increasing the use of double-stack trains.

This PPP will upgrade tracks, equipment, and facilities, and provide clearance for double-stack intermodal trains through three major rail corridors: the I-95 Corridor between North Carolina and Baltimore, Md., via Washington, D.C.; the I-70/I-76 Corridor between Washington, D.C., and northwest Ohio via Pittsburgh, Pa.; and the Carolina Corridor between Wilmington, N.C., and Charlotte, N.C.

Among the project’s goals is reducing road maintenance costs by converting more than 14 billion highway miles to rail. The benefits of this plan include improving safety, reducing CO2 emissions by almost 20 million tons, saving more than $3.5 billion in shipping costs, and reducing fuel consumption by nearly two billion gallons.

"The project began because we realized there will be a significant increase in the volume of freight moving in the United States over the next 20 years," says Robert Sullivan, director of media relations for rail carrier CSX Transportation. "The challenge is preparing the transportation infrastructure to handle the traffic."

SECURING THE FUNDING

CSX brought together a coalition of states—Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina—as well as shippers and shipper organizations. The states applied for $258 million in Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) grants, funded by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. These grants, which are awarded on a competitive basis, are supplementary discretionary funds for the National Transportation System, which appropriates $1.5 billion to invest in surface transportation projects that will have a significant impact on the nation or a metropolitan region.

The project will also secure $30 million from Ohio and $421 million from CSX and its affiliates. "The return on public investment is $22 for every one dollar invested, in addition to job creation and environmental benefits," says Sullivan.

The benefits to shippers are also significant, "as this project will open new markets and make them more accessible," says Sullivan.

One group of shippers that expects to get product to market faster and more cost efficiently is soybean farmers in Ohio, represented by The Ohio Soybean Council. More than half of the soybean crop is exported, and a growing percentage of those exports are containerized.

Currently, soybeans are shipped in containers from Ohio to Chicago, then railed to the West Coast. "The National Gateway Project gives us another way to get our product to market in containers," says Kirk Merritt, director of international marketing, The Ohio Soybean Council.

Ohio soybean farmers will be able to take advantage of a state-of-the-art intermodal terminal to be built in North Baltimore, Ohio. The farmers will double-stack product on containers in Ohio and transport them by rail to the North Baltimore terminal for export to Asia.

"Ohio is growing as a logistics hub, which benefits our industry," Merritt says. "Containerization provides an opportunity for farmers to control the quality of soybeans destined for Asia, as well as manage the supply chain more effectively by placing RFID tracking tags on the containers."

The National Gateway Project estimates that the new developments will enable one- to two-day service to the East Coast, as well as improved time to the West Coast. "Even a day or two can make a big difference," Merritt says.

The extent to which the National Gateway Project’s partners will benefit from their efforts is not yet known, but they have already begun to see results. A CSX Intermodal terminal began operations in September 2007 in Chambersburg, Pa., and the North Baltimore facility is scheduled to open soon.

The future promises new developments, as well. Work has already begun on 61 double-stacked rail clearance projects along the freight rail corridor. The balance of the upgrades will be completed as early as 2012, but no later than 2015.

New Routes Make Tracks: The Heartland and Crescent Corridors

Norfolk Southern (NS) hopes that the Heartland Corridor will do for it what the National Gateway will do for CSX. The Heartland Corridor is a PPP aimed at giving NS the ability to use double-stack containers, enhancing rail infrastructure and increasing freight capacity between the Port of Hampton Roads, Va., and the Midwest.

Before the Heartland Corridor project, Norfolk Southern’s most direct route to and from the Port of Hampton Roads had substandard clearances, requiring double-stack trains to take circuitous routes. In 2000, the wheels were set in motion to generate a PPP between the railroad and Virginia, Ohio, and West Virginia to raise 28 tunnel clearances on NS’s line.

During this time, ocean carrier Maersk Line built a $450-million terminal in Virginia to bring more containers through the port, increasing the container volume handled between Hampton Roads and the Midwest. In response, Norfolk Southern and federal and state governments jointly funded the $151-million Heartland Corridor project.

Due to be completed in June 2010, the Heartland Corridor will cut 200 miles and one day’s transit time from current rail routes. The benefits to the states are significant: Virginia gains an enhanced port and more direct double-stack service to the Midwest; Ohio taps into a new intermodal terminal in Columbus; and West Virginia will build its first intermodal facility, thanks to a land donation by Norfolk Southern. And, Norfolk Southern can better serve its customers.

"We were so pleased with the results of the Heartland Corridor that we decided to institute a PPP to help us deliver services we don’t currently offer," says Norfolk Southern’s Schafer. And so the Crescent Corridor was born.

While the Heartland Corridor was based on transporting international traffic to and from the port, the Crescent Corridor is focused on improving double-stack intermodal service for domestic freight between the Northeast and Southeast.

Public partners include Alabama, Tennessee, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Mississippi. In September 2009, the partners applied for a $300-million grant to help fund the project, which will improve a 2,500-mile rail network between the Northeast and Southeast.

During the past two years, NS has been working to eliminate chokepoints by adding main line tracks and new signal systems to accommodate more intermodal trains, thanks to early funding from the Commonwealth of Virginia. Future work will include laying additional track in other Crescent Corridor states, as well as modifying curves, constructing and expanding terminals, and running more efficient lanes.

These improvements will yield big public benefits, as they help trucks and trains—in partnership—capitalize on their strengths. For trucks, that means moving freight short distances; for rail, moving freight long distances. More than one million trucks annually will be absorbed from the paralleling interstates once the Crescent Corridor service is fully implemented, which will save 170 million gallons of fuel. Additionally, the Corridor will create an estimated 73,000 jobs by 2030, 47,000 of them by 2020.

The first Crescent Corridor trains are expected to be in operation by 2012.

PPP Funds Oregon Ports: The Infrastructure Finance Authority

Creating jobs through public-private partnerships is important to Oregon. So is securing state funding in support of those partnerships. That’s why Oregon formed the Infrastructure Finance Authority (IFA). The mission of the IFA is to ensure that the state’s infrastructure needs are identified and prioritized accurately to make the best use of its resources. Members of an independent IFA board, appointed by the governor, oversee the Authority.

The IFA helps Oregon communities build infrastructure and public facilities, and address their development needs by creating timely, fiscally responsible funding solutions, explains Lynn Schoessler, deputy director of Oregon Business Development and IFA director.

"PPP projects supported by IFA are becoming increasingly popular in Oregon because the state has limited financing resources," says Schoessler. "Neither the state nor its local businesses can fund infrastructure projects alone."

One key PPP project currently on the table in Oregon is financing a 2010 statewide port plan. The state’s legislators are interested in addressing the future needs of the ports and port activities.

"The IFA will subsequently fund local port projects to meet their individual objectives and to ensure that they comply with the state’s plans," says Schoessler.

Oregon’s 23 ports want to grow their existing business lines to include marine, air, and surface transportation; industrial property development; tourism and recreation; and marine-dependent facilities. The statewide Port Strategic Plan will act as a business guide to better define the relationship and accountability between the ports and the state.

The plan also seeks to create a state port investment fund, with financing components based on port size and market differences. The funds will address the state’s highest port priorities based on need, job creation, ability to advance Oregon’s key industries, and financial ability to operate and maintain the investment. The ports will be expected to issue periodic accounting reports on how they are using state grant funds.

The statewide port plan will address the negative cash flow occurring at many of the ports, support maintenance and infrastructure needs, and bring more jobs to the state as one in six Oregon jobs are tied to port activities or cargo.

Another Oregon port project expected to bring jobs to the state is the proposed relocation of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) from Seattle to the Port of Newport. NOAA has signed a 20-year lease to move its Pacific Research Fleet and new West Coast headquarters to Newport beginning in 2011. This deployment will relocate 175 crew members and 75 support staff and their families to the Oregon Coast.

"The positive economic impact of this decision cannot be underestimated and reflects the work of local economic development and port officials, as well as state legislators," says Schoessler.

U.S. Infrastructure: Worse for the Wear

When construction on the Interstate Highway System began in the 1950s, there were 65 million vehicles traveling 600 billion miles annually. Now there are more than 240 million vehicles, and they travel more than 3 trillion miles every year.

All this use has taken its toll on the country’s transportation infrastructure, as demonstrated by the figures below:

- 33 percent of America’s urban and rural roads are in poor, mediocre, or fair condition, according to the Federal Highway Administration.

- As of 2003, 27 percent of the nation’s 160,570 bridges were structurally deficient or functionally obsolete.

-

Naturally, these conditions have dramatic effects on Americans:

- Driving on roads in need of repair costs U.S. motorists $54 billion per year in extra vehicle repairs and operating costs—$275 per motorist.

- Outdated and substandard road and bridge design, pavement conditions, and safety features are factors in 30 percent of all fatal highway crashes.

Road use is expected to increase by nearly two-thirds in the next 20 years, making transportation infrastructure improvements crucial. The tremendous scope of this need, and the funding required, has inspired the growth of public-private partnerships.