Circular Supply Chains Go Round and Round

Circular supply chains can be resilient and sustainable, and can help meet growing demand for environmentally friendly products. But shifting from linear to circular supply chains requires intense research to determine how best to reuse many materials, implement new technology and processes, optimize returned goods, and educate suppliers and customers on circularity’s challenges and benefits.

Enterprises are doubling down on their commitment to circular supply chains, which use materials and goods as long as possible, instead of letting them go immediately to waste.

About 55% of organizations responding to a recent Bain & Company survey had made some commitment to circularity. “That number is much higher than it would have been in the past, and we expect it to go up,” says Hernan Saenz, global head of performance improvement and lead of the circularity practice with Bain.

“Circularity has accelerated significantly in the past three to four years, especially in the apparel industry,” says Marcus Chung, chief operating officer of Coyuchi, which, in 2017, became the first brand to launch a resale business in home textiles. In the past year or so, a few other brands have launched similar initiatives.

Circularity’s Benefits

Sustainability and circularity are important to value-driven consumers. Savvy brands are recognizing the growing business opportunity that comes with serving these customers.

Sustainability initiatives also help companies stay ahead of the expanding number of environmentally focused regulations.

For instance, in 2020, the European Commission adopted a circular economy action plan, which promotes circular economy processes, among other goals.

In the United States, almost half the states have implemented some type of extended producer responsibility legislation, the National Conference of State Legislatures reports.

By implementing solutions to quickly determine the optimal path for returned goods—say, whether to repair and offer them for resale or move them to a discount seller—companies can reduce expenses and boost sales as they enhance sustainability, says Tom Perry, CEO of G2 Reverse Logistics, which provides a reverse logistics platform.

Circular supply chains also tended to perform better than linear ones during the disruptions of the past few years. Because organizations have more control over input materials, circular supply chains can be more resilient. This will become increasingly important, given resource constraints and geopolitical tensions.

“In this world, controlling your inputs makes a massive difference,” Saenz says.

Circular Challenges

At the same time, executing a circularity approach isn’t easy. “It requires not just the adoption of new tools and signing agreements with suppliers, but also hinges on rethinking the levels of collaboration, redefining risks, and adding a new level of flexibility to planning,” says Inna Kuznetsova, chief executive officer of ToolsGroup, a supply chain planning and optimization firm.

Circularity often requires partnerships—at times, between direct competitors. For instance, it’s more efficient and easier for consumers if all electronics manufacturers collect every brand of used electronics than if each manufacturer accepts only its own products. Partnering with competitors, however, typically isn’t the natural way of doing business.

That may be changing, however, as companies realize they can’t solve circularity on their own. There are so many players who influence what happens within a supply chain for a given material or product.

“There’s more open-mindedness from brands about what that collaboration looks like,” says Cassie Gruber, director of business solutions for Jabil, a global manufacturing company that makes products for companies in multiple industries, including healthcare, automotive, and home appliances.

Some institutional investors have pushed back on circularity and sustainability initiatives, often out of concern over the time frames required to generate returns. “Circular supply chains are a long-term investment,” notes Abe Eshkenazi, CEO of the Association for Supply Chain Management (ASCM). In contrast, the investment community tends to measure returns in quarters.

Despite these challenges, a growing number of companies are implementing circularity initiatives and reaping multiple benefits. Here’s a look at some companies in action.

Textiles Bring It Home

Through its ReEntry program, which includes partnerships with independent recyclers, flooring company Interface reclaims used carpet tile and luxury vinyl tile and ensures that nothing ends up in a landfill.

Coyuchi, a provider of organic bedding, towels, and other home goods, has always embraced sustainability, Chung says. It crafts its products from organic fibers sourced from Fair Trade-certified suppliers, and its dyes are low-impact and natural.

With the launch of the 2nd Home Take-Back initiative, customers can return Coyuchi products when they’re ready to replace them. Through its Home Renewed recommerce program, Coyuchi, working with Bleckmann and Recurate, renews and offers for sale customers’ pre-loved Coyuchi items.

The renewal technology and solutions offered by Bleckmann, a provider of supply chain management services for fashion and lifestyle brands, enable Coyuchi to restore products to like-new condition. “Without their thorough cleaning and processing, we could not offer 2nd Home Renewed product to our customers,” Chung says.

Nicole Bassett, circularity lead with Bleckmann, and her team renew the products returned for resale, which can involve numerous manual processes, such as replacing buttons or cleaning. After the team completes these steps, each item is barcoded, inspected, and assigned a quality level. All information associated with the item is tracked and made transparent to the customer.

The data is also visible to the brand, which can leverage the data to determine, for instance, if some items need repairs more frequently than others. The products are packaged and placed into inventory to be resold.

One hurdle often is the product itself. Currently, few items are designed to be resold, Bassett notes. As a result, the only information available on a returned shirt might be its brand, size, and fabric content. A starting step for brands interested in circularity is to identify each product, ideally with a digital ID.

Until recently, 2nd Home Renewed was hosted on a site separate from Coyuchi’s main ecommerce site. This made for a less-than-ideal shopping experience. It also was challenging for Chung and his team, who were managing multiple sites, and separate marketing and other functions.

Coyuchi partnered with Recurate, which offers a tech-enabled resale service, to integrate 2nd Home Renewed into its main site, and now can offer customers a seamless shopping experience. Coyuchi also is better able to better understand customers’ behaviors, while introducing its main customers to the resale opportunity.

Coyuchi also is creating new products using post-consumer waste from returns. Its Full Circle Recycled Cotton Blanket is crafted, in part, from recycled cotton received through the 2nd Home program.

“It’s not easy bringing these products to life because the recycling infrastructure is still in its early stages, but we are excited to learn from our pilots and be ready to scale as the industry advances,” Chung says.

Construction Materials Build on Sustainability

The sustainable origin of Garnica’s products is based on the plywood producer’s commitment to sourcing wood from fast-growing tree farms, located in environments close to its production sites.

Garnica, a global plywood producer, has long employed sustainable, circular manufacturing and supply chain processes. “The good thing about wood products is that the raw material is renewable, recyclable, and captures carbon from the very beginning,” says Óscar Crespo, ESG officer.

Even so, Garnica goes beyond this. “We try to make our processes as circular as possible by, for example, using bio-based ingredients for some of the chemical components we use in our manufacturing process,” Crespo says.

For instance, for most wood products, the main use of energy is getting water out of the wood, as a log is about half water, Crespo says. Depending on the product being manufactured, the proportion or water needs to drop to between about 4% and 10%.

This typically is accomplished with the help of dryers. In North America, the dryers run largely on natural gas. Garnica, however, uses mostly biomass, which is a byproduct of its production processes.

Biomass is more complex to work with than natural gas and requires a greater capital investment. But this approach enables Garnica to use every part of the log.

In addition, biomass is carbon neutral from a C02 accounting perspective, as the carbon released is captured in tree growth. Garnica sells any wood that isn’t used for plywood panels or for producing energy to produce pulp for medium density fiberboard or particle board.

Garnica continues to research new uses for its wood, biomass, and other products. As with many research efforts, these often hit dead ends. “You invest a lot of time and resources, but you still might not get a product that’s marketable or scalable,” Crespo notes.

Interface, a flooring manufacturer, has recycled post-consumer carpet tile for more than 20 years. In 2023, it collected 5.7 million pounds of recycled carpet through its ReEntry™ Reclamation & Recycling program.

Based on the material’s condition and composition, products are diverted to their most sustainable option, such as reuse, recycle, or energy recovery, says Liz Minné, head of global sustainability strategy.

Interface also uses recycled and bio-based materials in many parts of its carpet tile, resilient, and rubber products. Today, 51% of the materials used to make Interface products are from recycled or bio-based sources; for carpet tile, the percentage is 66%. Nearly 40% of the materials used to make Interface LVT (luxury vinyl tile) and other resilient flooring are from recycled or bio-based sources, with the use of recycled fillers. The bio-based content includes renewable plant-based material.

At the same time, challenges and roadblocks remain when creating a truly circular economy. Interface continually collaborates with its supply chain partners to identify scalable and circular supply chain solutions. “As a part of our updated carbon strategy, we plan to expand our use of low carbon materials by partnering with new and existing suppliers who might have additional innovative materials we can substitute into manufacturing processes,” Minne says.

Educating and engaging suppliers so they understand and can reduce the carbon footprint of their operations and materials is a critical step in reducing the environmental impact of Interface’s supply chain, Minne adds.

Recycling Energy

CarbonQuest, a carbon management company, enables buildings to capture carbon dioxide (CO2) generated from their heating, power, and other building systems. It then uses the recycled CO2 product in environmentally beneficial ways.

For example, it may sell liquified carbon dioxide to concrete manufacturers who use it in their products, says Anna Pavlova, senior vice president, strategy, market development, and sustainability. New ways to use CO2 to replace petroleum continue to emerge, as well.

Few building managers are familiar with this carbon capture technology, which makes education critical, Pavlova says. For instance, facilities professionals may not realize that many buildings can be retro-fitted to incorporate carbon capture solutions. The solutions are modular and can be installed indoors and/or outdoors, and will fit in most basements, rooftops, and/or on pads outside a building.

With some larger installations that currently use heating systems like CHP (combined heat and power) or fuel cells, a carbon capture solution can be one-fifth to one-tenth the cost of electrification, Pavlova says. The solution often can bolt onto fuel cell or co-generation solutions.

To match the carbon that has been captured with potential users, Pavlova and her team have built extensive partnerships with CO2 users and distributors. When determining which use case makes sense for a particular CO2 capture, she considers the volume and the organization’s CO2 needs. She also factors in the distance to deliver the product, as the goal is to remain as local as possible. Carbon Quest then engages its partners to jointly develop a program for the offtake.

Packaging Plays a Part

“Massive innovation is happening in packaging,” says Hernan Saenz, lead of the circularity practice of Bain & Company.

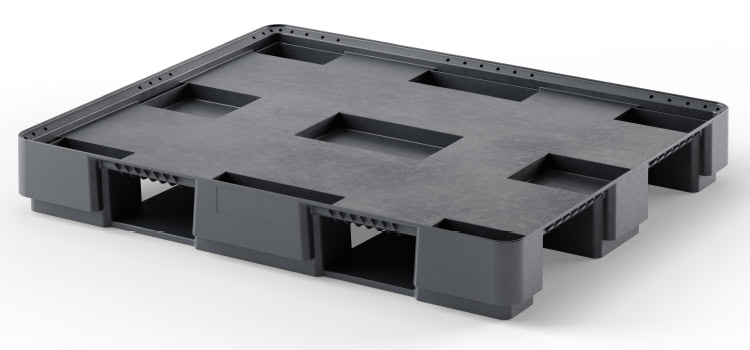

Consider Cabka, which produces pallets and containers made largely with post-consumer and post-industrial waste and scrap (photo above). About 90% of its parts are made from recycled material, says Jean-Marc Van Maren, chief product officer. Cabka also recycles the pallets and containers that come back from customers.

That said, working with recycled materials is “not so easy,” Van Maren notes. For instance, Cabka’s continued efforts to make its units lighter and better, while ensuring they meet stringent specifications, requires substantial engineering and testing. “Each pallet must meet multiple requirements, such as carrying heavy loads, being safe to handle, and withstanding different temperatures and rough handling,” he adds.

Cabka invests time upfront to understand the requirements of its customers, and often, its customers’ customers. Next steps include creating designs and making small prototypes and 3D prints, before making the real pieces. These are tested to check that they can be used in different settings, such as with robots and/or AGVs.

Another challenge is ensuring a stable supply of recycled product streams. When working with companies to take their recycled material, Cabka has to understand how much of the material will become available. If the materials vary greatly, it can lead to a lot of differentiation in the recycled products, Van Maren says.

Tosca provides crates, pallets, and other reusable plastic packaging, typically for food and food ingredients, that can be used between 80 and 150 times. Many of the products also are collapsible, which cuts down on transportation costs and energy use. At the end of their lives, the containers are ground up and used to create new containers, says Karin Witton, global director of sustainability.

Compared to a corrugated cardboard box—the typical alternative—Tosca’s products usually emit fewer greenhouse gases. They also use less water, despite the cleaning required before the containers are reused, Witton says.

When researching new sources of plastics, Tosca has to ensure the materials it’s considering are food-safe. It can be difficult to determine the source, grading, and other attributes of some ocean plastics, which can limit their usability. “All of that has the potential to be a problem,” Witton notes.

Jabil Builds a Circular Solution

In 2021, to help determine its five-year sustainability goals, Jabil surveyed internal and external stakeholders, including suppliers and customers. “The two areas stakeholders were focused on were climate and circular economy,” says Cassie Gruber, director of business solutions.

This information prompted Jabil to set a goal of engaging in 10 circular economy projects across various industries by 2026. The company’s progress is audited by a third party and publicly disclosed in its annual sustainability report.

In 2023, Jabil acquired Retronix, an electronic component reclamation and refurbishment company, to help it manage products that reach the end of their lives.

“Retronix can remove soldered or embedded chips and components from printed circuit boards (PCBs) that still have value,” Gruber says. The chips and components might be redeployed back to the customer or liquidated in the secondary market, prior to the board being recycled. Retronix also can refurbish the reclaimed chips and components through reballing, retinning, and testing. When a chip or component re-enters the market, it is prepped and ready to go directly back onto manufacturing lines.

“That adds an additional layer of value and reliability for electronics brands looking to prolong the product’s lifespan, reduce the need for new products, and decrease carbon emissions,” Gruber says.

For large cloud customers, Jabil developed a circular solution for data centers that have reached the end of their lives, and after all reuse options have been exhausted. The boards are shredded and milled to be recovered for precious metal value and recirculated into supply chains. This Design-to-Dust solution can be deployed on-site anywhere in the world. Because the boards have been converted to powder, there is no risk of data extraction.

Some customers approach Jabil seeking a circular economy, but the type of circularity varies. Some prefer items not go back out into the supply chain, or they don’t want it back themselves. Then Jabil must find a place for it elsewhere in the value chain. The nuances to creating a circular economy that’s right for a company vary, due to regulations, organizational policies, and what’s feasible economically, among other factors.

“When it comes to circular economy, none of it is cookie-cutter,” Gruber says.