Robots in the Supply Chain: The Perfect Employee?

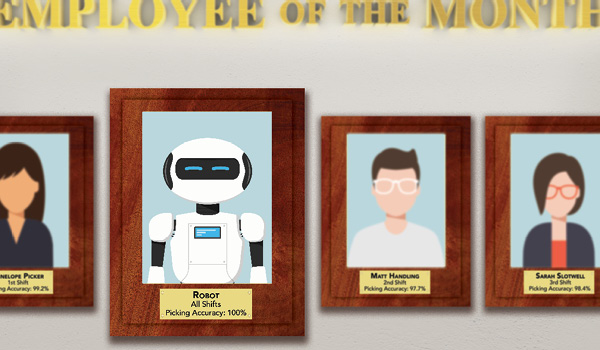

Robotics systems help distribution facilities gain speed, increase accuracy, cut costs, and handle the grunt work so employees can focus on more productive tasks. And no resume or job interview required.

We’re sitting in the middle of a perfect storm for robots in the supply chain.

Distribution Center of the Future

E-commerce sales continue to climb, forcing retailers to pick up the pace in their fulfillment and distribution centers. But these days, it’s hard to find workers to keep product moving in any kind of warehouse—e-commerce or otherwise. With U.S. unemployment at 4.1 percent as of January 2018, people aren’t exactly lining up for low-paying, repetitive jobs that often require miles of foot travel per shift.

“Many businesses in the United States and worldwide are facing labor shortages,” says Joel Reed, vice president of IAM Robotics in Sewickley, Pennsylvania. Baby boomers are retiring, and younger workers are less inclined to spend their work hours walking and picking.

“We are having issues with finding and retaining employees for second shift picking,” confirms Gary Ritzman, project manager at Rochester Drug Cooperative (RDC), a distributor that uses two IAM robots in its New York distribution center.

Even when companies can find warehouse workers, some positions see a great deal of turnover. “They’re just not good jobs,” admits Matt Wicks, vice president of product development at Honeywell Intelligrated in Mason, Ohio. “They’re prone to injury, and a lot of them are not in the best environments.”

Robots for logistics are designed to take over the supply chain’s least attractive tasks. In some cases, robotic systems do this work entirely on their own, freeing humans for more complex functions. In other instances, bots collaborate with humans. Whatever the scenario, proponents say that these automated solutions provide a big productivity boost.

Companies use robots throughout the supply chain. Manufacturing is the traditional venue, but these days, you might even see robots in retail locations. Walmart, for example, has been testing bots that roam the sales floor scanning shelves in 50 of its stores.

But many new developments focus on the warehouse. There, robotic solutions fall into at least three categories: bots that deliver product from place to place; bots that pick, insert, or otherwise manipulate items; and bots that do both.

From Place to Place

In the first category, Bleum Robotics in Englewood, Colorado, offers a low-built robot that lifts a shelving unit from a densely packed storage area and transports it to a picking station. There, following instructions on a screen, a human picks items from the shelves into slots on a “smart rack.” The robot then returns the shelves to storage.

Bleum’s software keeps the robots from colliding as they carry shelves around the building. “Essentially, it’s the same algorithm that air traffic controllers use,” says Eric Rongley, the company’s CEO. When the bots travel unloaded, they mostly scuttle beneath rows of shelves.

Bleum also offers a larger robot that can move product by the pallet load. “Workers take the pallets off a truck, move them to a storage area, and then have the big robots bring those pallets to a replenishment station where workers put items onto shelves,” Rongley says.

In addition, Bleum might one day adapt its robots for use in factories, where they would offer a less-expensive alternative to automated guided vehicles (AGVs) that run on tracks. “AGVs cost $80,000 to $100,000, while the robots cost about $25,000,” Rongley says.

For the warehouse, Bleum’s main selling point is the efficiency gained when autonomous machines bring goods to pickers. “The automation reduces warehouse operational expenses by anywhere from 60 to 80 percent,” Rongley says.

Locus Robotics, based in Wilmington, Massachusetts, takes an inverse approach. Instead of bringing product to a human picker, Locus’s model assigns a human to a picking zone filled with product. A bot brings a set of instructions, waits while the person picks the desired items, and then carries that product away.

Each Locus robot uses three main technologies to navigate around the building. First, before a unit goes to work for the first time, it creates an internal map of the layout of the warehouse. Second, the robot uses odometry to measure distance travelled. Third, it uses onboard LIDAR to autonomously navigate the space, allowing the robot to actively “see” obstacles and moving objects and adjust its travel path. Lastly, the robots are able to communicate with each other to share and report traffic, obstacles, and congestion, allowing the bots to plot optimal travel paths for maximum speed and efficiency.

“A moving robot fuses that information together, and then it knows its location,” says company CEO Rick Faulk. “It also looks out for forklifts, humans, or other obstacles.”

Locus uses a “robot as a service” business model. “Instead of paying a human $18 hourly, companies now hire a robot and typically pay about $4 per hour,” Faulk says.

Optimizing People Power

Quiet Logistics, which offers e-commerce and omnichannel fulfillment, uses Locus’s bots to keep up with customer demands for fast, accurate service in a tight labor market. “We’d rather have the people working in our fulfillment business do more productive tasks, such as personalization and customization,” says Brian Lemerise, president of Quiet Logistics in Devens, Massachusetts. “We let the robots drive around 14 miles per day.”

When Quiet opened for business in 2009, it used robots from Kiva Systems. It turned to Locus after Amazon purchased Kiva in 2012 and took those robots off the market. Quiet currently uses the bots in its two Massachusetts facilities and will add them to its St. Louis fulfillment center in late 2018.

Currently, Quiet uses four or five robots for each human stationed in its picking zones. A worker patrols a zone of about five aisles, waiting for a robot to arrive with a picking assignment. As the human approaches, the robot scans the worker’s ID badge. “It greets them in their native language with a nice user interface that includes photos, and tells the worker which unit to pick from what location,” Lemerise explains.

The worker places the item in a bin that the robot carries, using a scanner on the robot to capture the barcode. The robot then moves on to its next location, and the worker looks out for the next robot.

In its second Massachusetts facility, where Quiet never used the Kiva system, productivity is now three to five times better than in the pre-robot days, Lemerise says.

Lending a Hand

For another type of robot, the work is largely about picking up and putting down.

RightHand Robotics offers a stationary robot for picking individual items, such as those shipped in e-commerce orders. A company can use it for tasks that were previously impossible to automate—for example, to move product from bins on a conveyor system into cartons, or onto a sorting system, or to assemble separate products into kits.

The robot takes instructions from a warehouse management system (WMS). “The information we receive is similar to what you’d get from a pick-to-light system: how many items to pick, where to pick them from, and where to place them,” says Leif Jentoft, co-founder of the company, based in Somerville, Massachusetts.

Robots with grabber arms have been lifting and placing items in factories for years, but piece-level picking in a warehouse presents a tougher challenge. Instead of handling the same components repeatedly, the RightHand system might have to pick thousands of different items, in all sizes and shapes.

The RightHand robot uses 3D optics to recognize objects; it uses feedback from sensors in its grippers, and artificial intelligence, to improve its technique over time.

RightHand’s robots help companies fill orders reliably, in spite of the tight labor market. They also improve picking accuracy. “A person on a picking line gets tired and eventually starts making mistakes,” Jentoft says. “The robots don’t.”

A company using RightHand’s technology typically would assign human associates to more complex tasks that the robots can’t perform. “These tasks include making sure the systems are operating effectively and looking across the whole warehouse to identify what is functioning, what is not functioning, and what needs to be done if there’s an issue,” Jentoft says.

Honeywell Intelligrated provides fixed robots as part of integrated material handling systems that include other automation equipment, such as conveyors. Certified by the Robotics Industry Association, Honeywell Intelligrated offers bots for a variety of uses, such as case packing and unpacking, each picking, stacking mixed SKUs onto a pallet, palletizing and depalletizing, and stacking and wrapping pallets in a single process.

In some cases—for instance, in some examples of each picking—human pickers may work in the same general area as Honeywell Intelligrated’s robotic arm. Some items, such as products with complex shapes that tend to become intertwined, are just too difficult for robots to handle. “But robots are getting good at handling many different types of objects individually and effectively,” Wicks says.

The robots use computer vision and machine learning technologies to locate and manipulate individual items in all their variety. They rely on other systems to send them only the kinds of products they can handle appropriately, while routing other items to human pickers. “The conveyance, the sortation, the sequencing—those types of other ancillary systems become very important when you look at applying robotic each picking as an order fulfillment solution,” Wicks says.

Robotic systems improve efficiency by removing human error from a variety of tasks. A robot can also outperform a human in tasks that require heavy lifting, such as loading a pallet. “Handling full layers at a time and stacking them onto another layer is uniquely suited for robots,” Wicks notes.

For some tasks, such as depalletizing, robots are faster than human workers. But even when they’re not faster, robots often get more done over the course of a shift. “When you consider the robot is available to operate 24/7, with no breaks and less down time than an operator would have, they don’t necessarily need to be faster,” Wicks says.

Pluck and Roll

At RDC’s facility in Rochester, the robotics solution from IAM teams human workers with robots that both travel and pick. The drug distributor currently has two IAM robots, each working an eight-aisle pick zone on the DC’s mezzanine, which is devoted to slower-moving products.

“Each aisle has six bays of shelving, plus an end cap,” Ritzman says. “The robot runs parallel to a conveyor system and then makes a right-hand turn to go into one of the aisles.”

In each zone, a human operator takes shipping totes from the conveyor, scanning the barcode on each to send picking instructions to the robot partner. The robot travels the aisles with a picking tote, using a suction cup on its arm to pluck items off the shelves. It then returns to the human worker, who scans each item, transfers it to the shipping tote, and places that tote on a second conveyor, bound for a shipping station.

IAM Robotics uses 3D navigation and vision technology to help its robots navigate the aisles and spot the products they are supposed to pick. The robot receives orders through a wireless connection and then disconnects from the network, traveling autonomously.

Before the robots go to work in a facility, the IAM system uses a unit called Flash, which it terms “a high-performance, combination product dimensioner and photo booth,” to scan an example of each SKU.

“We get all the item information from the UPC code,” Reed says. “We collect the item’s weight, and then we get three-dimensional data on height, weight, and depth. Finally, we get a high-resolution image of that product.” When it comes time to pick, the bot uses this information to recognize the items it needs.

RDC still uses human associates to pick faster-moving items and pharmaceuticals, to do case picking, and to pick unwieldy items, such as wheelchairs. But the robots have reduced the number of associates the company needs on the mezzanine.

“Currently, we project that one operator will be able to handle the two robots and free two other people to do something else, to help us finish faster,” Ritzman says. “One person can make the difference between finishing on time or late.”

Some observers envision a future when robots will take over nearly every job in a warehouse. But for now, at least, workers and logistics robots are divvying up the work, focusing on the jobs each does best to keep product flowing quickly and correctly.

Distribution Center of the Future

What will happen when the latest robotics technologies mature and become widely available? DHL provides one possible snapshot of our future:

Compared with the distribution centers of today, the robotic warehouses of our future are likely to improve in almost every metric. These highly scalable facilities will be more flexible and faster to relocate; they will achieve higher productivity with increased quality.

New operations will incorporate different types of robot, each with a specific job to perform such as unloading trucks, co-packing, picking orders, checking inventory, or shipping goods. Most of these robots will be mobile and self-contained, but they will be coordinated through advanced warehouse management systems and equipped with planning software to track inventory movements and order progress with a high degree of accuracy.

Overall reliability will increase because there will be fewer “single points of failure” in each distribution center. As each robot acts as an individual unit, we will be able to quickly push it to the side if it breaks down and replace it with another unit from the robot fleet. Depending on the problem, we will be able to fix the broken robot on site, or send it to a central repair facility. The new robot will be connected to the cloud so it will automatically download the knowledge needed to take over from its decommissioned counterpart.

Warehouse workers will be given more responsibility and higher-level tasks such as managing operations, coordinating flows, fixing robots, and handling exceptions or difficult orders. They will wear exoskeletons to help them lift heavy goods with less strain, fatigue, and chance of injury. When necessary, we will bring goods into a co-packing area where collaborative robots will work safely alongside highly skilled warehouse employees to transform basic products into new items customized for individual orders.

Employees will train the robots through simple interfaces to do easy and repetitive tasks, and these humans will take on the more challenging work themselves. Both small and large warehouses will enjoy productivity gains as we add—as needed—the robots that have proved to be successful in supporting the existing workforce.

Workers will be able to flex and scale operational capacity according to changing demand simply by adding more robots to cover peaks and automatically removing them from the building (relocating them to where they are next needed) to rebalance the distribution network. And we will experience the emergence of a robot leasing, rental, and pre-owned market, allowing companies to reduce capital investments while further increasing operational flexibility.

SOURCE: Robotics in Logistics, DHL Trend Research